It’s been a tiring two weeks. True, I’ve been sleeping until noon while the rest of you engage the enemy (I mean, ahem… go off on practicum), but you must understand that my guilt over the whole thing has exhausted me completely. That must be why it took me a few cups of coffee and several replays to appreciate this campaign ad for the Green Party of Ontario.

Get it? ‘Grey’ is Progressive Conservative. But he reminds me of ‘PC’ from the Apple ads! One abbreviation…two different guys… but they’re both squares! Yuk, yuk, yuk! Who says Canadian politics can’t be fun!?

Alright, so what am I on about? Well, there is a provincial election in Ontario on October 10th, and the place of religion in public schools has become an important issue for voters. Should faith-based schools be eligible to receive public funds, providing they adhere to the Ontario curriculum and hire licensed teachers? The aptly-named John Tory, leader of the Progressive Conservatives, says aye. Frank de Jong, leader of the Greens, says nay. And the Liberal incumbent Dalton McGuinty seems content with the status quo, which is a terribly awkward mixture of his opponents’ positions. That is, presently in Ontario, the only religious schools which receive public funding are Catholic schools.

As those of us enjoying the Policy Course know, the funding of the Catholic schools is protected under our Constitution, which in 1867 assured all pre-existing religious schools the right to continue in this tradition. In fact, in 1997 when Quebec sought to reorganize its school boards by classifying them linguistically rather than denominationally, the government had to petition Ottawa for a constitutional amendment allowing for the dissolution of the Protestant and Catholic boards. Newfoundland also asked for and received such an exemption in 1998 so that it could abolish its denominational school system. Today, Ontario is the only province in Canada which continues to fund its Catholic schools to the exclusion of other faiths; every other province either funds all religious schools equally or funds none of them.

The question of how to correct this apparent injustice is not a new one for Ontarians. In 1984, after a decision to extend even more funding to the Roman Catholic high schools, Premier Bill Davis appointed a commission to investigate whether the province’s other faith-based schools should receive public funding. After an extensive one-year study, the commissioner Bernard Shapiro presented a report which suggested that the government extend some public assistance to the private schools, and he included recommendations on how to execute this plan. (As an interesting aside, Shapiro would later become Principal of McGill University, from 1994 to 2002.)

It is perhaps unfortunate that the Ontario government did not act on these recommendations. In 1999, the United Nations Human rights Committee ruled that Ontario’s policy of funding only the Catholic schools is discriminatory, in violation of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which Canada ratified with the consent of all provinces, in 1976. In 2005 the committee censured Canada yet again, for failing to "adopt steps in order to eliminate discrimination on the basis of religion in the funding of schools in Ontario."

What humiliation! Clearly, something must be done. But what? Should the province withdraw public support from the Catholic schools in order to create one public, secular system (as is the case in New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland)? Or should the province extend partial or full funding to all religious schools (as is the case in Quebec, Alberta, British Columbia, Saskatchewan and Manitoba)?

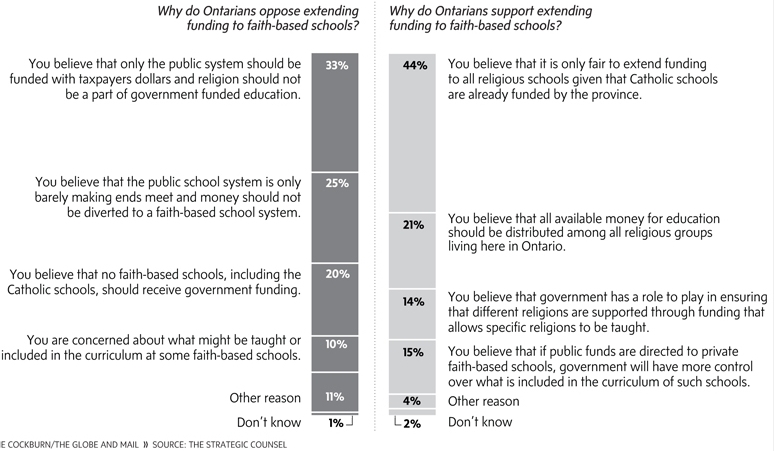

If anything, Ontarians are leaning towards the latter. This poll reports that 71% of those surveyed oppose the funding of faith-based schools. An especially helpful component of the poll was a breakdown of the reasons for which the respondents answered the way they did (click for larger image):

Of the reasons for opposing faith-based education, I find the spending priority argument to be the least convincing. That is, if religious schools are deserving of public funds, they are deserving of them whether or not those funds are scarce. If there is a burden to be borne, let it be borne equitably, or else let us fund the schools properly.

More interesting to me is the argument that in principle, religion should not be a part of public education and therefore should not be a taxpayer expense. Of course, by funding faith-based schools the taxpayers would not be paying for religious indoctrination in its own right, but rather for an education adhering to the guidelines of the provincial curriculum, being taught in a religious environment. Let us make that very clear; it is an important distinction. Still, mixing religion with taxpayer dollars tends to put people on edge. For instance, when I brought this topic up in conversation a friend of mine scowled and declared, "Separation of Church and State!"

As a self-labelled Godless Liberal, I liked the sound of that. I still like the sound of it, even though I don’t think it works in this context. Canada adopts a policy of religious pluralism, not atheism. If we are to accept that religion is an integral component of culture, and if we embrace a philosophy of multiculturalism (using the Canadian Multiculturalism Act as our guide to building a society cohesive with this philosophy), then does it not follow that we should recognize and support the religious traditions of our communities? Doesn’t imposing secular education on every child (that is, on every child whose parents can’t afford to pay upwards of $600 per month in tuition) contradict our deepest convictions about the value of diversity?

I find these questions very compelling. We expect our government to promote multiculturalism – it is one of the defining ideas of our nation. But to deprive the public educational system of unique schools, diverse schools, specialized schools and yes, secular schools as well (for it is essential to have the correct balance) is I think, to deprive our society of an enormous opportunity for richness and equity.

There is an interesting counterargument, however, which deserves some attention. To wit, a secular school system is essential for a multicultural society to function well. The secular schools provide a common touchstone for a diversity of citizens, giving children of different backgrounds and beliefs a common experience. This commonality and familiarity, presumably, fosters tolerance, and certainly we must recognize that tolerance is of paramount importance. If it is true, as Dalton McGuinty suggests in his campaign video, that funding the religious schools would result in the kind of segregation that would harm the social cohesion of the very multicultural society we wish to propagate, then Tory’s plan must be viewed with great reticence.

But in truth, I do not find McGuinty’s argument entirely convincing. Right now about 30% of Ontario students attend publicly-funded Catholic schools. Has this caused so much damage that the 2% of students who currently attend schools of another religion cannot be accommodated? Surely, Montreal is one of the best examples of a successful multicultural society, and this city has the highest percentage of private schools in North America (in Quebec, the figure is 30%; on the island, it is much higher). I hypothesize that the status-quo is more detrimental to Ontario’s multicultural mosaic than any alternative could be. The blaring unfairness of funding only the Catholic schools probably breeds resentment on the part of minority groups, and rightly so!

In the following video, John Tory makes the argument that the opportunity to receive public funding would act as an incentive to faith-based schools to teach the Ontario curriculum. It is a good point. Right now there are 53, 000 students attending private, faith-based schools with little or no government oversight. Would it not be better to encourage these schools to adopt the standards of education that all other Ontarian students enjoy?

It is possible that my position on this issue is influenced by my own history of having been educated in a Catholic secondary school. I can say with conviction that I did not experience any feelings of segregation. On the contrary, I found the experience culturally enriching. Though, I do not credit the doctrines of Catholicism with the excellence of my schooling; I credit the teachers entirely, and the sense of community and spirit of charity that the faith indirectly encouraged in The Girls. I know some of my former classmates who were much more enriched spiritually than I was. I know others who didn’t like the atmosphere at all, and transferred to another school.

You see, it is not my position that a religious education is preferable to a secular one. What I do believe that it is right to give parents and students the choice. I think that we can have a public school system that is as diverse as the society it seeks to educate, and that there is more than one way to educate a child to the academic standards that Ontario requires of its secular schools. I think that all schools who achieve this standard of academic instruction should be eligible to join the public education community.

To me, this is a very Canadian idea. That is, in my Canada, it is not enough to promote multiculturalism in secular schools while in the same breath imposing that same kind of secularism on everyone who wants a public education. In my Canada, a religiously-minded family does not have to choose between financial security and giving their child an education that reinforces their culture and values. In my Canada, multiculturalism is not whatever results from pooling all the students together into one type of learning environment and calling it “equality,” even if that learning environment is ill-suited for some of those students. Rather, multiculturalism in my Canada flourishes naturally because of public policy that promotes strong communities of diverse citizens who feel welcomed and valued. This is the kind of welcome that fosters patriotism for a new home - or in my case, for an old one. This is the kind of welcome that I would be proud to extend, as a Canadian, to all those who want to be Canadians, too.

2 comments:

Hi Kristen,

I would recommend that you seek a venue to publish this piece. Well thought out and articulated.Nicely done.

L.

You were right then, Canadian politics can be fun, you just have to find it.

=p

Post a Comment